The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee is a fascinating read about the journey scientists have traveled to unlock the mysteries of the gene, the master code that defines all forms of life. As with his Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, Mukherjee interweaves dramatic stories about scientific discoveries and patient journeys with approachable scientific explanations.

The book begins with the story of Mendel’s discovery of heritable traits in pea plants in 1864 and traces the timeline through the hypotheses, horrors, and exciting advances over time to where we stand today in the era of genomics. Mukherjee writes in the prologue: “This book is the story of the birth, growth, and future of one of the most powerful and dangerous ideas in science: the ‘gene,’ the fundamental unit of heredity, and the basic unit of all biological information.”

He intertwines his personal quest to find answers about the likelihood he may one day suffer from the mental illnesses that have burdened some of his family members. It’s a worry many of us can relate to — whether we will fall victim to health problems that have affected our relatives, or that we may pass on to our children.

Four things I liked or appreciated learning more about in The Gene:

1. Mukherjee doesn’t pull any punches tackling important ethical questions. At the outset, he dedicates the book to Carrie Buck, who was sterilized by tubal ligation in October 1927 following a court order that deemed, “…The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes.” He covers the eugenics movement in the United States, which predated the horrors of Nazi eugenics in the 1940s which then accelerated the atrocity from sterilization to mass murdering the “genetically sick,” and “racial cleansing.”

Later, he writes about the ethics discussions that took place at the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA (Asilomar II, California, 1975). He writes,”Scientists were alerting themselves to the perils of their own technology and seeking to regulate and contain their own work.” This reminded me of similar discussions at the recent International Summit on Human Gene Editing held in Washington, D.C. Leading scientists and bioethicists from around the world convened to discuss the ethics of editing the human germline with CRISPR, a recently discovered tool that can edit DNA. Today, we can both sequence the entire human genome and change it permanently. Mukherjee writes, “It hardly requires an advanced degree in molecular biology, philosophy, or history to note that the convergence of these two events is like a headlong sprint into an abyss.”

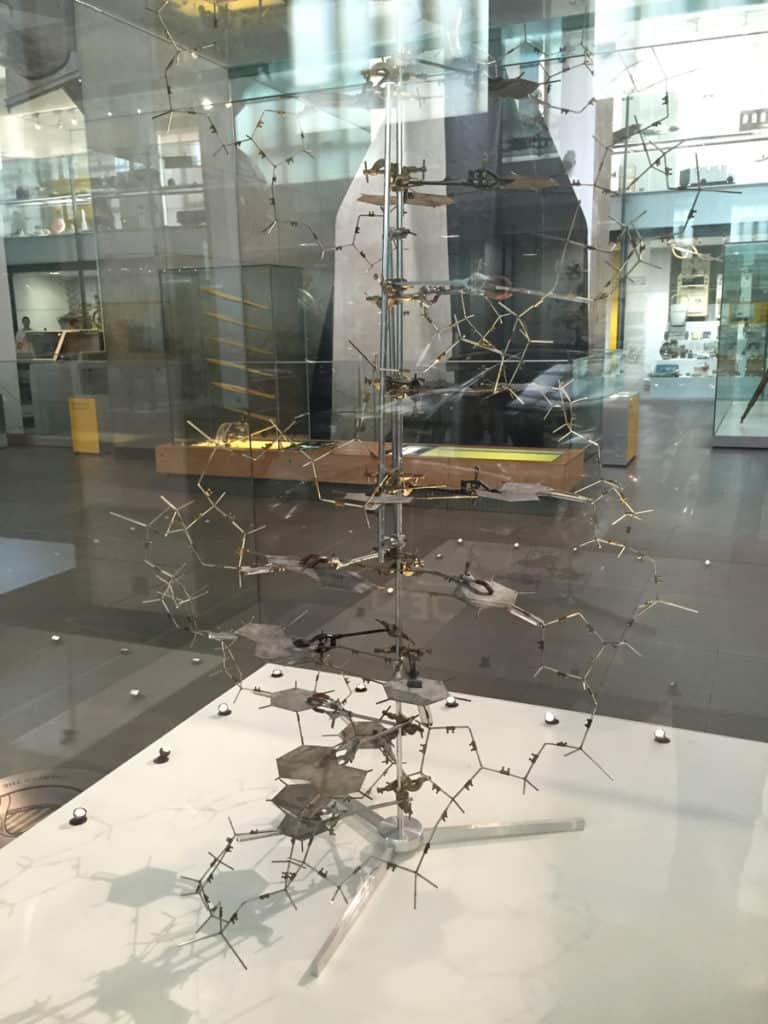

2. Rosalind Franklin’s contribution to the discovery of the structure of DNA in 1953. Many overlook Franklin’s contribution, her pivotal Photo 51 that showed the double helix structure. She missed out on sharing the Nobel Prize awarded to Francis Crick and James Watson in 1962, as she passed away at the age of 37 in 1958 from metastatic ovarian cancer. Here is a picture of Crick and Watson’s original model of the double-helix nature of DNA. I was excited to see it on a visit to the Science Museum in London, UK but disheartened to find it stuck between exhibits of the automobile and the steam engine in the Making the Modern World gallery. The first model of the code of life deserves a much better place of honour!

Crick and Watson’s DNA model on display at the Science Museum, London UK

3. Classifying people by race is meaningless on a genetic basis. We can scan the human genome to look for insights about where our ancestors came from, as some of my friends have done recently through home DNA tests from AncestryDNA or 23andMe. But classifying people by racial groups to make genetic predictions is a fool’s errand. The human species is too young to have accumulated substantial genetic divergence. Mukherjee writes, “The vast proportion of genetic diversity (85 to 90 percent) occurs within so-called races (i.e. within Asians or Africans) and only a minor proportion (7 percent) between racial groups. For race and genetics, then, the genome is a strictly one-way street. You can use the genome to predict where X or Y came from. But knowing where A or B came from, you can predict little about the person’s genome.” Further, since mitochondrial DNA is passed on to children only from mothers, we can all trace our lineage to a single female, “Mitochondrial Eve,” who theoretically lived in Africa about 200,000 years ago.

4. Mukherjee’s writing makes the science of genetics delightfully approachable. Before I read the book, I had a basic understanding of heritable traits from high school biology class. Beyond that, I have had the opportunity to learn more while writing stories on genetics like Family Learns Health Secrets Through Genome Sequencing, Brave New World: Are we ready for human germline gene editing? and by attending talks to learn about epigenetics and how CRISPR may one day be used to treat inherited disorders. But there was so much more to learn about genetics in The Gene. I loved the deep dive, and I am in awe about how much there is still left to discover.

Have you read The Gene: An Intimate History? I’d love to hear your comments.

Every generation produces variants and mutations. Here is an example in my garden.