Given that fall is just around the corner and those of us who live in northern latitudes are heading back into the seasons where we will have little to no chance to get natural vitamin D from the sun, I am revisiting a story I wrote more than a year ago: Vitamin D: Pros and Cons.

Vitamin d hype and debate continue

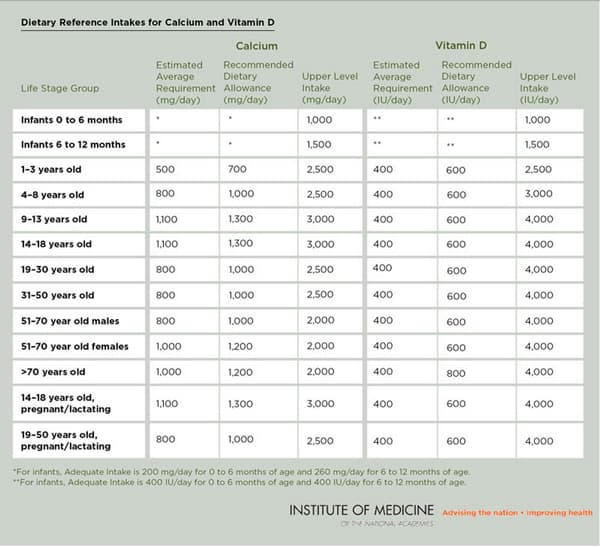

This past spring, large ads in Canadian newspapers claimed that no one is getting anywhere close to the amount of vitamin D needed and that we should increase our intake by 10-fold, from the 600-800 international units daily recommended by Health Canada (and the US Institute of Medicine), to a whopping 6,000-9,000 international units per day.

Canadian registered dietician Leslie Beck wrote in The Globe and Mail, “Osteoporosis experts are being inundated with calls from confused patients. Dietitians of Canada has expressed its concern in a letter to Health Canada. And Canadians are wondering what to make of the bold assertion that Health Canada was wrong and that we actually need more – a whole lot more – vitamin D to ward off disease. Do we?”

Those ads, placed by Pure North S’Energy Foundation, claimed that vitamin D deficiency is causing widespread illnesses and premature deaths. According to this story in The Globe and Mail, wealthy entrepreneur and chemical engineer Allan Markin, who claims he has invested $20 million in Pure North S’Energy Foundation, personally takes 12,000 IUs of vitamin D daily.

Measuring media hype about vitamin D

In a recent paper, Timothy Caulfield and colleagues examined the media coverage of vitamin D and how its role in health and the need for supplements were portrayed. Caulfield is a Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy and a Professor in the Faculty of Law and the School of Public Health at the University of Alberta. The paper was published in BMJ Open and a full copy is available here. The researchers surveyed 294 print articles from elite newspapers in the UK, US and Canada over a 5-year period and found that newspaper coverage generally:

- supported supplementation for the general population

- framed vitamin D as difficult to obtain from the food supply

- asserted that vitamin D deficiency is a widespread public health issue

- linked vitamin D to a wide range of health conditions for which there is no conclusive scientific evidence

- downplayed the limitations of the existing science

- overlooked the potential risks of supplementation

It’s no surprise to me that these researchers found 40 different health conditions mentioning a relationship to vitamin D. As I wrote a year ago, there is a flood of observational studies linking vitamin D deficiency to cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, autism, kidney disease, multiple sclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, gum disease, arthritis, premenstrual syndrome, all-cause mortality and on it goes.

Health journalist André Picard wrote in The Globe and Mail that claims about vitamin D being a miracle drug that can prevent a wide range of illnesses are ridiculous: “These are preposterous claims based on the dubious premise that by hiking the amount of vitamin D in our blood, a broad range of illness would disappear,” and “the fundamental error here is confusing correlation and causation. Yes, people with adequate vitamin D levels have less disease. But it does not follow that pumping everyone full of supplements will make them healthier. Enthusiasm for this panacea simply doesn’t match the scientific evidence.”

Correlation is not causation. Still!

Yes indeed! As any health journalist worth their salt understands, the problem with observational studies is that we only learn that two things changed when we looked at their data together, NOT that changes in one of them caused changes in the other. [If you want to better understand how ridiculous it is to draw causal conclusions on observational data, check out Tyler Vigen’s Spurious Correlations, which started as a blog and is now available as a book. It’s hilarious!]

No matter how much readers or editors want to read about “dramatic new studies” to justify their beliefs that popping large amounts of vitamin D daily will improve their health or ward off a host of diseases, the truth is that answers about vitamin D’s effectiveness and safe upper intake levels can never be found in observational studies. Nor can we discern how much vitamin D people should take based on how far away from the equator they live (yes, that was a real question I was asked to field).

Best evidence on the horizon

So where do things stand? As far as I can tell, the same as they did a year ago. There is still no conclusive evidence that taking vitamin D supplements provides benefits beyond bone health — yet.

JoAnn Manson, MD, DrPH, Chief of Preventative Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School (and who was on the IOM Committee that developed the current public health recommendations) said a year ago that the enthusiasm for vitamin D supplementation continues to outpace the evidence. She said that the evidence to date shows some vitamin D is good, but more is not necessarily better. There is limited research on long-term intakes above 2,000 IU daily and with very high doses of 10,000 IU daily or higher, people can develop a high level of calcium in the blood or urine, which can cause cardiovascular problems and kidney stones.

The best evidence on the horizon, as far as I can tell, is still the VITAL study (VITamin D and OmegA-3 Trial). Led by Dr. Manson and colleague Julie Buring, ScD, it’s a large-scale, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective trial with an impressive design. The test groups and the comparison groups are designed to have a large enough difference in vitamin D levels to see if there is a meaningful difference in health outcomes. The study began in 2008 and results are expected in late 2017. I’m optimistic that this study will shed light on understanding how altering levels of vitamin D supplementation impacts on health conditions beyond bone health.

It may not be palatable for those looking for a panacea to wait until late 2017, but strong, evidence-based science takes time.